A frequency list is simply a list of the most frequently used words in a language, ranked from the most frequent to the least frequent.

As you might already be wondering, such lists can be a useful tool for language learners, especially if they’re absolute beginners in a given language. Someone who wants to become fluent cannot learn only the vocabulary related to their interests; they also need more general knowledge of the language. And what is a quicker way to acquire this general knowledge of your target language? In my opinion, using frequency lists.

Instead of learning random vocabulary, you can target the words that will have the greatest impact on your overall language proficiency.

Some people like the idea of learning the most frequently used words, while others do not.

But those who don’t like it argue that, because these words are used so frequently, they will be learned over time.

But why wait? Why not learn them right from the beginning, so you can start reading texts, building vocabulary, and learning through comprehensible input as soon as possible? “Why actively study a language if we can learn it through exposure alone?” Yes, it is possible—I learned English that way myself. But why do it? Why take so much longer when you can actively study and learn those words more quickly?

At first, the argument that learning should happen over time discouraged me from deliberately studying the most common words in Russian.

But studying the most commonly used words does make sense. After all, they’re the most frequently used words! Do I really need to say something else? Learning the most frequently used words made so much sense to me that I couldn’t help but ignore that argument and try it anyway.

And so I decided to give it a try anyway, and the results were great!

I started to understand many of the things I read on the internet, entire messages and social media posts. I know that this boost in my Russian came from studying the most common words, since the phrases I encountered were made up largely of the very words I had learned. It felt almost like that great moment when you realize you can already understand a new language fluently.

Learning the most common words marked a clear turning point in my journey with the Russian language.

It can be divided into a before and after focusing on those words.

This is why I highly recommend learning the most common words in your target language.

You can learn “harder,” unfamiliar words and unusual sentence structures, but if native speakers rarely use them, why bother? You likely won’t encounter those words or structures again, and therefore won’t internalize them. But when you study less used words that are still among the most frequently used, you expand your useful vocabulary (and therefore won’t forget).

That weak objection should not have discouraged me from using a frequency list, especially considering that I strongly support active study.

To write this post, I spent some time on Reddit reading the arguments of those who are against using frequency lists, and now I’ll address them and share my perspective.

Another common argument against actively studying the most common words is that learning words in isolation isn’t a good idea.

I agree that learning words in isolation is not a good idea, but we need to keep in mind that learning the most frequently used words is not the same as learning words in isolation.

- Learning words in isolation is one thing;

- learning high-frequency words is another.

Why do we need to blend the two?

Just because you’re learning words from a frequency list does not mean you have to study them in isolation. You can learn these words through sentences and meaningful context. It is not impossible. A language tutor—or you, if you know how to work with a foreign language—can create short phrases using those same common words. This way, you learn important vocabulary while also learning how to use it.

At the beginning, even though the phrases are natural and correct, they may sound awkward—and that’s okay!

This happens because of the limited vocabulary at the beginning, which is completely normal and expected. We simply can’t express very deep or precise ideas with only a few words. For example, “You and I are people” is a correct and natural sentence in English, but it still sounds awkward. It’s an awkward statement. It makes your listener think, “Are you stupid? Of course we’re people. Why are you saying this?”

For me, the purpose of those dumb phrases isn’t so much to make you learn the phrase itself, but to help you understand the meaning and usage of a word.

For example, let’s say you’re learning the word “and.” In the sentence “You and I are people,” the sole purpose is to show that “and” is used to connect two or more elements of the same grammatical type. In this case, it links two subject pronouns—both among the most common words (“you” and “I”)—to form a compound subject. As you can see, it’s much easier to understand how “and” works by seeing it in a sentence than by simply hearing an abstract explanation of its usage.

As you progress through the frequency list, you’ll be able to start forming more useful phrases.

I can create sentences for my students that not only sound natural but are also useful and actually used by native speakers in everyday conversations. These are natural sentences composed exclusively (yes, exclusively) of those initial common words. Some of these sentences even contain idiomatic expressions. So, no, creating sentences made up solely of the most common words does not mean they are unnatural or not actually used by speakers of a language.

I tried using AI to generate sentences with the most common words I provided from the frquency list, but the results weren’t satisfactory.

The sentences didn’t sound natural and many of them didn’t even make sense. But again, the problem wasn’t the frequency list itself. Afterwards, I created the sentences myself using those same words from the frequency list, and they sounded natural, were actually used by native speakers, and even included idiomatic expressions.

Of course, creating sentences takes some time.

It would have taken more time if I had been creating those sentences in a language I didn’t know.

This brings us to another common objection to using frequency lists in language learning: it takes time.

Well, creating any study material requires time and effort. Self-learners pay with time. One option you may consider is buying time by hiring a tutor, who—besides helping in other areas of language learning—can also save you time by creating natural, correct sentences for you. The next time you learn a new language, you’ll already know how to create them on your own faster. If you don’t have the money yet, you probably have the time, and that time can be used to prepare your study material.

Most of the initial part of frequency lists consists of function words (articles, prepositions, and the like), which is another reason some people are against using frequency lists.

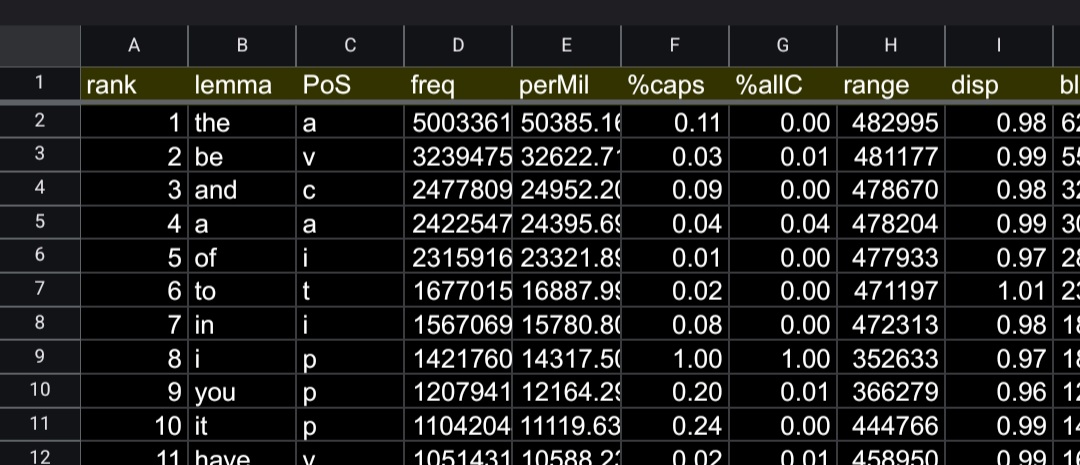

In fact, you can’t form a sentence by simply combining “the,” “be,” “and,” “a,” “of,” “to,” and “in” (the seven most frequently used words in English, in that order). These are function words, not the meat of a sentence. But this is an important point to keep in mind: you do not have to learn common words by strictly following the order of a frequency list. You can learn the first few words (usually articles and prepositions) and then move on to nouns, adjectives, and verbs, which appear further down the list.

After that, create the sentences using those words.

Then learn a few more of the first words and move on to adding more nouns and adjectives.

The point is that you don’t need to limit yourself to function words just to follow the sequence.

In sum, as you can see, the objections consist basically of critics on poor use of frequency lists, not the use of frequency lists themselves.

As you can see, in summary, these objections are basically criticisms of poor use of frequency lists, not of frequency lists themselves.

For them, there seems to be only one way of doing things, and anything outside of it is seen as impossible or not allowed. It’s as if they’re saying, “No, to learn the most common words, you HAVE to memorize them in isolation!! We’re not allowed to do it in any other way!”

No, I can learn those words in context and sentences.

Another argument is that learning the top 100 or 300 most frequently used words won’t make anyone fluent.

Of course!

Of course, learning those words isn’t enough to make anyone fluent. That’s not the point.

Learning the most frequently used words is just the beginning of your language learning journey. It’s only one part of it.

The goal is to reach a level where you can actually use the language you’re learning. You can get there faster by focusing on the most frequently used words (as well as the words you often encounter and would use related to your personal interests). Once you reach this level, you can start using your target language, paving the way toward fluency.

The frequency list is just one piece of the puzzle, not the entirety of your language learning journey.

And even if you already know all the words from the beginning of the list, I still recommend spending some time on them to learn and master their actual pronunciation.

Many polyglots use frequency lists and see great results.

Once the problems some people impose to this approach are set aside, only the benefits—benefits that even critics acknowledge—remain.